Questions 11-21 are based on the following

passage.

This passage is adapted from David Rotman, “How Technology Is Destroying Jobs.” ©2013 by

MIT Technology Review.

MIT business scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and

Andrew McAfee have argued that impressive

advances in computer technology—from improved

industrial robotics to automated translation

5 services—are largely behind the sluggish

employment growth of the last 10 to 15 years.Even

more ominous for workers, they foresee dismal

prospects for many types of jobs as these powerful

new technologies are increasingly adopted not only

10 in manufacturing, clerical, and retail work but in

professions such as law, financial services, education,

and medicine.

That robots, automation, and software can replace

people might seem obvious to anyone who’s worked

15 in automotive manufacturing or as a travel agent.But

Brynjolfsson and McAfee’s claim is more troubling

and controversial. They believe that rapid

technological change has been destroying jobs faster

than it is creating them, contributing to the

20 stagnation of median income and the growth of

inequality in the United States. And, they suspect,

something similar is happening in other

technologically advanced countries.

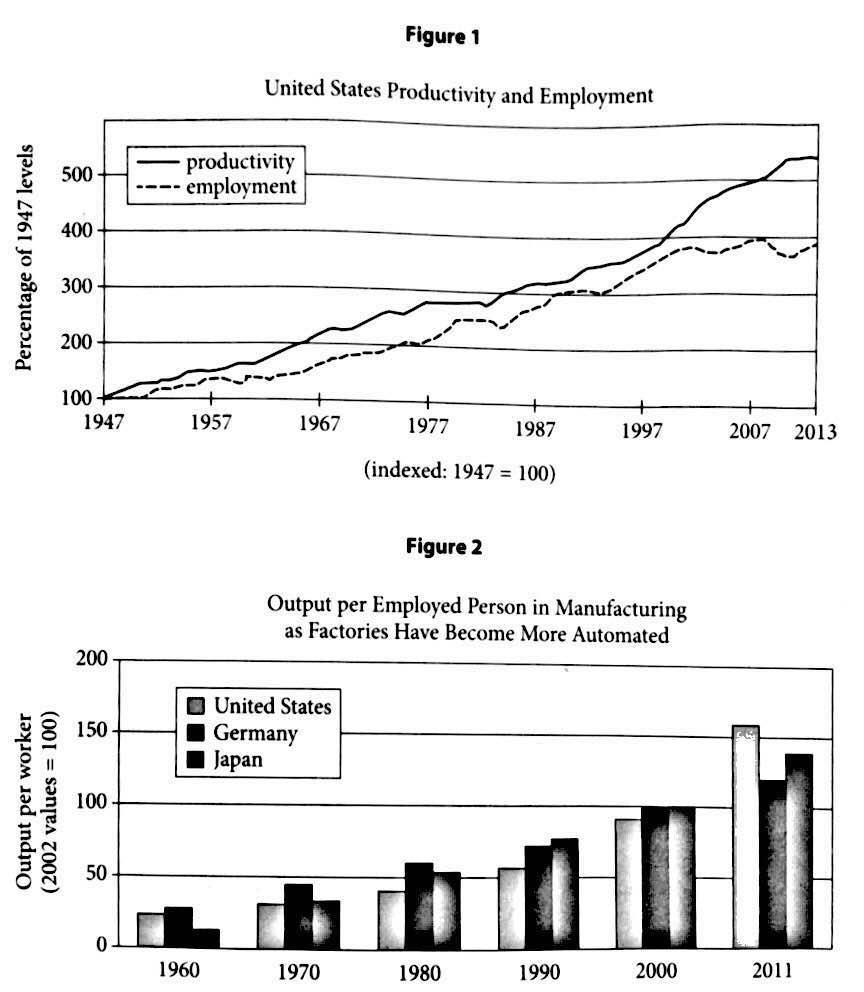

As evidence, Brynjolfsson and McAfee point to a

25 chart that only an economist could love. In

economics, productivity—the amount of economic

value created for a given unit of input, such as an

hour of labor—is a crucial indicator of growth and

wealth creation. It is a measure of progress. On the

30 chart Brynjolfsson likes to show, separate lines

represent productivity and total employment in the

United States. For years after World War II, the

two lines closely tracked each other, with increases in

jobs corresponding to increases in productivity. The

35 pattern is clear:as businesses generated more value

from their workers, the country as a whole became

richer, which fueled more economic activity and

created even more jobs. Then, beginning in 2000, the

lines diverge; productivity continues to rise robustly,

40 but employment suddenly wilts. By 2011, a

significant gap appears between the two lines,

showing economic growth with no parallel increase

in job creation. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call it the

“great decoupling.” And Brynjolfsson says he is

45 confident that technology is behind both the healthy

growth in productivity and the weak growth in jobs.

It’s a startling assertion because it threatens the

faith that many economists place in technological

progress. Brynjolfsson and McAfee still believe that

50 technology boosts productivity and makes societies

wealthier, but they think that it can also have a dark

side: technological progress is eliminating the need

for many types of jobs and leaving the typical worker

worse off than before. Brynjolfsson can point to a

55 second chart indicating that median income is failing

to rise even as the gross domestic product soars. “It’s

the great paradox of our era,” he says. “Productivity

is at record levels, innovation has never been faster,

and yet at the same time, we have a falling median

60 income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling

behind because technology is advancing so fast and

our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.”

While technological changes can be painful for

workers whose skills no longer match the needs of

65 employers, Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist,

says that no historical pattern shows these shifts

leading to a net decrease in jobs over an extended

period. Katz has done extensive research on how

technological advances have affected jobs over the

70 last few centuries—describing, for example, how

highly skilled artisans in the mid-19th century were

displaced by lower-skilled workers in factories.

While it can take decades for workers to acquire the

expertise needed for new types of employment, he

75 says, “we never have run out of jobs.There is no

long-term trend of eliminating work for people. Over

the long term, employment rates are fairly

stable. People have always been able to create new

jobs. People come up with new things to do.”

80 Still, Katz doesn’t dismiss the notion that there is

something different about today’s digital

technologies—something that could affect an even

broader range of work. The question, he says, is

whether economic history will serve as a useful

85 guide. Will the job disruptions caused by technology

be temporary as the workforce adapts, or will we see

a science-fiction scenario in which automated

processes and robots with superhuman skills take

over a broad swath of human tasks? Though Katz

90 expects the historical pattern to hold, it is “genuinely

a question,” he says. “If technology disrupts enough,

who knows what will happen?”