Questions 11-21 are based on the following

passage.

This passage is adapted from Jeffrey Mervis, “Why Null Results Rarely See the Light of Day.” ©2014 by American Association for the Advancement of Science.

The question of what to do with null

results—when researchers fail to see an effect that

should be detectable—has long been hotly debated

among those conducting medical trials, where the

5 results can have a big impact on lives and corporate

bottom lines. More recently, the debate has spread to

the social and behavioral sciences, which also have

the potential to sway public and social policy.

There were little hard data, however, on how often or

10 why null results were squelched. “Yes, it’s true that

null results are not as exciting,” political scientist

Gary King of Harvard University says. “But I suspect

another reason they are rarely published is that there

are many, many ways to produce null results by

15 messing up. So they are much harder to interpret.”

In a recent study, Stanford political economist

Neil Malhotra and two of his graduate students

examined every study since 2002 that was funded by

a competitive grants program called TESS

20 (Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences).

TESS _allows_ scientists to order up Internet-based

surveys of a representative sample of US adults to test

a particular hypothesis (for example, whether voters

tend to favor legislators who boast of bringing federal

25 dollars to their districts over those who tout a focus

on policy matters).

Malhotra’s team tracked down working papers

from most of the experiments that weren’t published,

and for the rest asked grantees what had happened to

30 their results. _In their e-mailed responses, some

scientists cited deeper problems with a study or more

pressing matters—but many also believed the

journals just wouldn’t be interested. “The

unfortunate reality of the publishing world [is] that

35 null effects do not tell a clear story,” said one

scientist._ _Said another, “Never published, definitely

disappointed to not see any major effects.”

Their answers suggest to Malhotra that rescuing

findings from the file drawer will require a shift in

40 expectations._ “What needs to change is the

culture—the author’s belief about what will happen if

the research is written up,” he says.

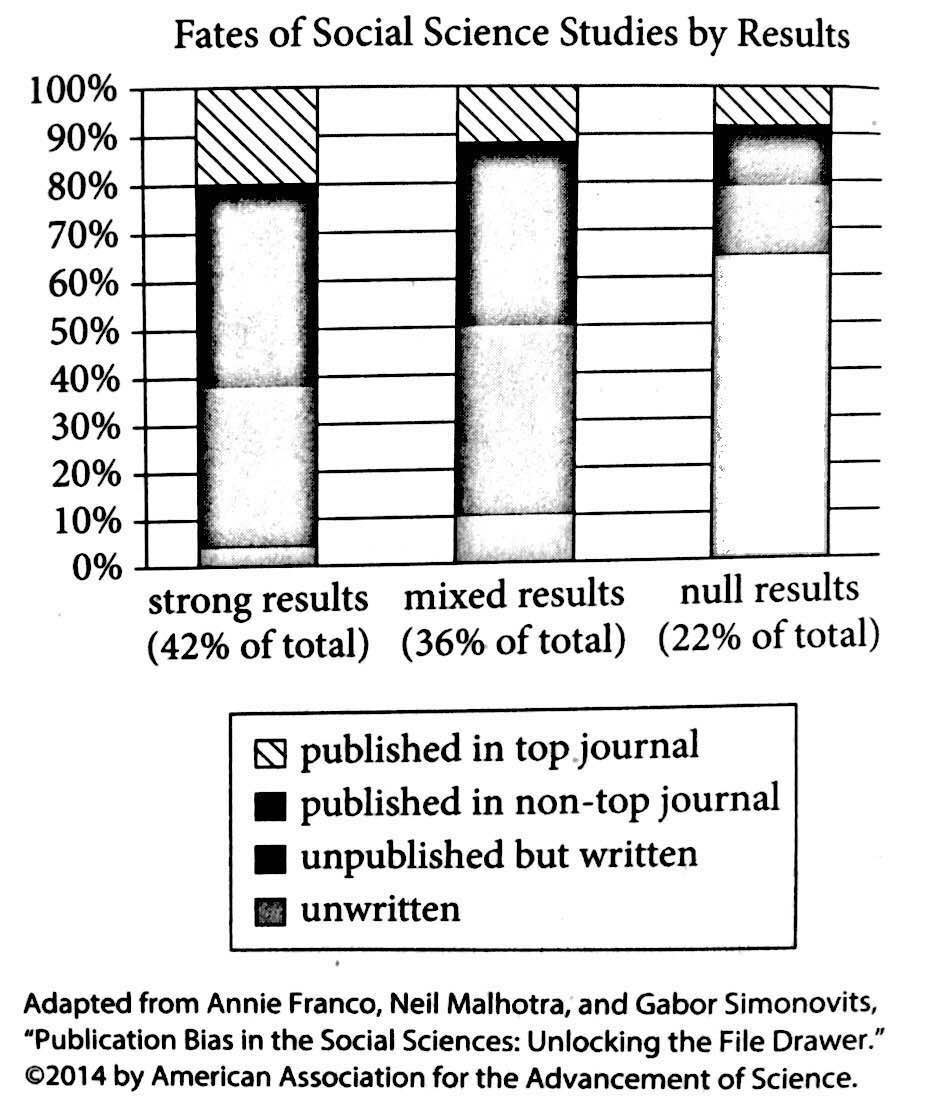

Not unexpectedly, the statistical strength of the

findings made a huge difference in whether they

45 were ever published._ _Overall, 42% of the experiments

produced statistically significant results. Of those,

62% were ultimately published, compared with 21%

of the null results._ _However, the Stanford team was

surprised that researchers didn’t even write up

50 65% of the experiments that yielded a null finding.

Scientists not involved in the study praise its

“clever” design. _“It’s a very important paper” that

“starts to put numbers on things we want to

understand,” says economist Edward Miguel of the

55 University of California, Berkeley.

He and others note that the bias against null

studies can waste time and money when researchers

devise new studies replicating strategies already

found to be ineffective._ _Worse, if researchers publish

60 significant results from similar experiments in the

future, they could look stronger than they should

because the earlier null studies are ignored.Even

more troubling to Malhotra was the fact that two

scientists whose initial studies “didn’t work out”

65 went on to publish results based on a smaller sample.

“The non-TESS version of the same study, in which

we used a student sample, did yield fruit,” noted one

investigator.

A registry for data generated by all experiments

70 would address these problems, the authors argue.

They say it should also include a “preanalysis” plan,

that is, a detailed description of what the scientist

hopes to achieve and how the data will be analyzed.

Such plans would help deter researchers from

75 tweaking their analyses after the data are collected in

search of more publishable results.